Travels in Morocco: Preserving the Past, Protecting the Future

Published 03/26/2025 in Scholar Travel Stipend

Written

by Marcela Correa |

03/26/2025

For our little family of three, travel is a pathway to a meaningful life. While providing us with adventure, entertainment, and many unforgettable experiences, travel also sheds light on global issues. For our end-of-year vacation, we chose Morocco as our destination. Morocco attracted us with its diverse landscapes, rich history, and vibrant culture.

Arriving to Casablanca, Morocco’s financial powerhouse and main gateway to the country, we headed straight to Marrakech and, after spending a few days exploring the narrow streets and bustling souks of this ancient city, we began a two-week private tour guiding us southeast across the Atlas mountain range towards the Sahara desert (Aït Benhaddou, Ouarzazate, Skoura, Merzouga) and, from the outskirts of the closed border with Algeria, headed back North (Fez, Meknes, Chefchaouen) and West (Rabat) to finalize the tour where we began. While taking in the rich colors, sounds, smells, and flavors offered to us at every step of the way, we also set out to investigate how Morocco is attempting to develop sustainable tourism strategies that benefit both the environment and local communities, with an emphasis on balancing economic growth and preservation.

Tourism is one of Morocco's primary economic drivers, contributing significantly to GDP and employment. According to the Moroccan Ministry of Tourism, the sector accounts for nearly 7% of the country’s GDP and provides jobs for hundreds of thousands of people. However, unregulated tourism growth can lead to negative consequences, such as over-tourism, environmental degradation, housing displacement, pollution, and cultural erosion. Sustainable tourism seeks to mitigate these risks by promoting responsible travel practices, protecting natural and cultural heritage, and ensuring economic benefits are distributed equitably among local communities. Given the central role played by tourism in Morocco, exploring how it can be made more sustainable ties into the Milken Institute's mission to accelerate progress in both economic and environmental health.

In Marrakech and Fez, we experienced staying in a riad, a traditional Moroccan house or palace with an indoor garden and courtyard, located within the old city (“medina”) walls. Once homes to wealthy merchants and traders, riads are an excellent example of conservation–repurposing and revitalizing traditional dwellings to suit new demand and new uses. By celebrating the cultural heritage inherent in these properties, locals and investors have created demand for them as mid to high-end accommodations. Further into the desert, in regions dominated by the Amazigh, we observed a type of fortified residence called “kasbah,” typically built of clay, straw and stone. Some kasbahs have been repurposed as hotels, as one located in the small oasis village of Skoura, or as museums, like the immense one located right at the center of the city of Ouarzazate. Many of them are in an irreversible state of disrepair that makes them outright inhabitable, but we were relieved to witness ongoing efforts to preserve and, in some instances, repair historic buildings dating as far back as the eleventh century.

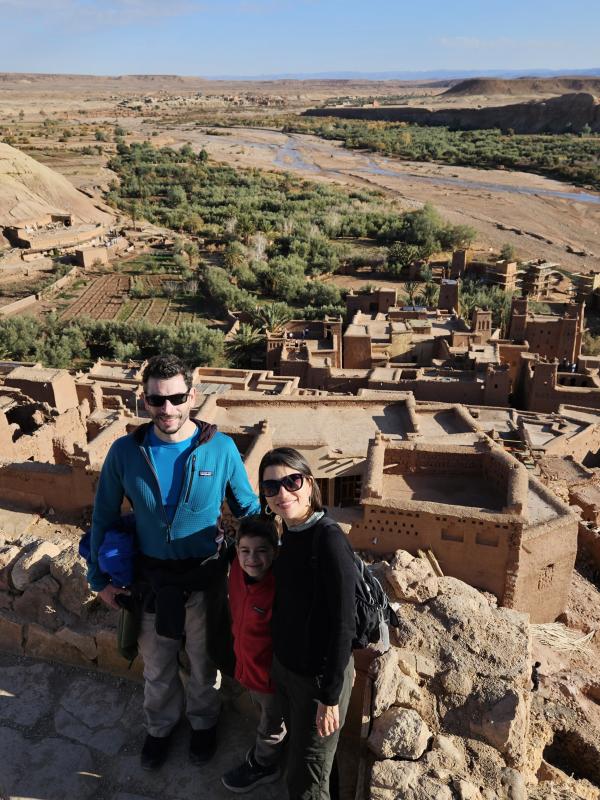

Another great example of preservation intertwined with modern initiatives for economic sustainability is posed by Aït Benhaddou, a historic “ighrem” or “ksar” (fortified village) along the storied caravan route from Timbuktu in Mali, across the Sahara to Marrakesh. While considered a great example of Moroccan earthen clay architecture, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, it has found new life, not only as a tourist site in itself, but as backdrop for many cinematic blockbusters! We saw the ongoing construction of an open air movie set at the outskirts of the historic site. In that same place, scenes from the “Gladiator” movie were filmed 25 years ago. In fact, the nearby city of Ouarzazate has become, in the meantime, the site of sprawling film studios, offering an excellent example of a well developed, niche industry that exploits the advantages of what the land has to offer, with productions broadly ranging from Roman (“Gladiator”), Egyptian (“The Jewel of the Nile”, “The Mummy”) and Middle Eastern (“Lawrence of Arabia”, “Jesus of Nazareth”) themes to fantastical ones (“Games of Thrones”). An expansive film studio in such a remote, unsuspecting place, was an outstanding example of how to leverage environmental, cultural, and historic assets to support the local economy, develop business opportunities, and in this case, launch a new self-sustaining industry.

Further along our counter-clockwise tour across Morocco, we had the opportunity to observe other large-scale preservation efforts, part of an initiative by King Mohammed VI to renovate 17 historical sites to drive tourism and, in turn, create jobs and demand for local artisans. Meknes, located in Northern-Central Morocco and one of the country’s four “imperial cities,” struck us by the magnitude of the public works campaign to preserve and renovate its historical sites. Particularly impressive were those of the Royal Palace, the underground prison of Qara, the Imperial Granaries, and Bab Mansour gate, which served as the ceremonial entrance to the Kasbah of Sultan Moulay Isma'il. We also encountered ongoing preservation work at the Roman ruins of Volubilis and a ruin complex in Rabat that spans different eras and cultures, from Roman to Amazigh to Muslim, and even older remains of phoenician settlements being currently excavated along the shores of the nearby Bou Regreg river.

While we most witnessed the correlation between tourism, architectural preservation, and economic growth, there were similar linkages to cultural preservation. Morocco is a unique place in the way artisanship (leather, bronze, pottery, mosaic, weaving, woodwork) is alive and thriving, fully interwoven in the socio-economic fabric of everyday activities, with tourism being one of the sustaining pillars. Returning to Casablanca for our flight back home, our Moroccan trip had one last, eye-opening surprise. Located in the heart of the city overlooking the Atlantic ocean, we visited the Hassan II Mosque, a living monument to Moroccan artistry. It is estimated that six thousand traditional Moroccan artisans worked on the construction and decoration of the mosque, with both structural design and decor being tightly interwoven. The mosque is a masterpiece of stonework, metalwork, carpentry and wood carvings, and traditional Zellige tilework. The building is a public demonstration and celebration of Moroccan culture, emphasizing to tourists and locals that cultural preservation is respected, valued, and income-generating.

We had a magnificent time in Morocco, learned about the country and its people, and have a deeper appreciation for how tourism can contribute to preservation, rather than exploitation, of local cultures and sites. We look forward to supporting similar efforts in our future travels.

*Amazigh is the indigenous and culturally-appropriate term for a collective of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa. The term berber was a derogatory name introduced by Roman invaders but has remained in use to the modern day.